A "Bonsoir" Story

Sponsored, patronised, and initiated by France, "Bonsoir" went on to become one of the most recognisable programmes in Sri Lankan television history. This year it celebrates its 40th anniversary.

“As I sat down to write this story, I had neither a beginning nor an end. I just had an incoherent and disjointed trickle of memory which silently flowed through my fingers, across the keyboard, and into the hard drive of my computer.”

Kumar de Silva, The Bonsoir Diaries (2013)

I first came across Kumar de Silva through his mother. Mrs Manel de Silva was a terror at my school, at least in Grade Three, but she taught me and inculcated in me a love for history and English literature that has stayed with me ever since. She was also a lady of habit, and one habit she always had was to carry a Bonsoir pencil case. It stayed on her desk, all the time, and it constantly caught my eye. I was too afraid to ask her what it was, so I went back home and asked my mother instead.

That was when I was introduced to Bonsoir, the French Embassy sponsored programme that ran for a quarter-century on ITN and introduced to Sri Lankans a world they could not otherwise access. Kumar de Silva took the lead in the programme for its first 15 years, to the extent that Bonsoir became Kumar and Kumar became Bonsoir.

This month and this year, Bonsoir celebrates its 40th anniversary. Looking back, I realise much has changed. But the memories of that programme still linger, as does the memory, however fleeting, of Mrs Manel and her pencil case.

For those of the social media generation, and the AI generation, Bonsoir appears almost like an anomaly. But for those of us who grew up in those times, a half-hour weekly programme was only way one could gain access to a foreign culture and society. Travel was hideously expensive then, and it was still the first few years of the Open Economy: that grand, ambitious plan which turned Sri Lanka into a middle-class Fantasia. We aspired for more, and television made us aspire for even more.

It was against this backdrop that the French Embassy in Colombo felt the need for a cultural programme which could bolster ties between the two countries. The history of French engagement in Sri Lanka is neither a long nor a happy one, as Yasmin Rajapakse – who co-hosted Bonsoir with Kumar – has observed in her book on the De Lanerolles.

Yet the reforms of the 1980s dismantled the socialist experiment of the 1970s and introduced television to Sri Lanka. The French were clearly taking a risk in sponsoring a programme about French culture in a country where all things English still reigned supreme. But it was a risk they felt worth taking, and after a while, it worked.

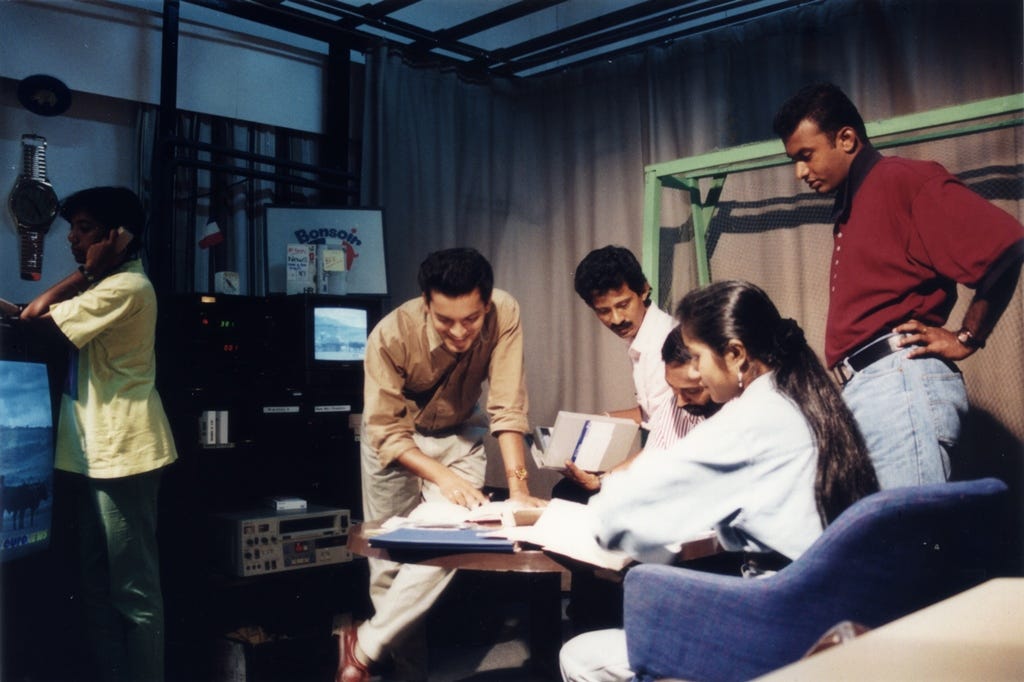

The Bonsoir Diaries (Samaranayake Publishers, 2013) tells the story of Bonsoir’s genesis, so I shall not waste time recounting it here. Suffice it to say that by the time Kumar entered the studio, the show had gone off to a rocky start. Logistically, it was a nightmare, and it took time for Kumar and his team – Yasmin Rajapakse and Chinthananda Abeysekera – to get settled. While it was shot initially at the ITN studios, it soon acquired a life of its own.

In this the producers had to put up, as Kumar reminds us, with the most primeval of settings. The creativity that they put into those initial episodes simply cannot be replicated today. From reenacting “chilly Strasbourg” under a hot, sweltering tropical sun and touring the south of France along Rosmead Place, they made the best use of what they had.

From the beginning, the creators knew they were trying the impossible: popularise French culture, art, and society in a country where relatively few were fluent even in English. Yet the programme took off, and in a few years, it became so popular that, as Kumar remembers in his book, a Sinhala Bonsoir came to be. I sadly do not recall anything of the Sinhala Bonsoir, but Kumar and Yasmin let it have its own shelf life, and it led a life of its own until Bonsoir as a whole “died” – Kumar’s word, not mine – in December 2010.

Perhaps the programme’s greatest achievement lay in its recognition of the fundamental premise of cultural diplomacy, reciprocity. Bonsoir was about French culture, yes, but it was equally about Sri Lankan culture.

One of the most beautiful episodes that Kumar recounts in his book revolves around food: bouillabaisse in France, ambul diyal in Sri Lanka. Cinema, language, literature, the common experiences of people across time and space: these were aspects Bonsoir probed. The result is that today, French language and cultural programmes remain enormously popular in Sri Lanka: to give one example, the Alliance Francaise, the premier French-language teaching institution here, is based not just in Colombo but also in Kandy, Matara, and Jaffna: basically, across the island.

25 years later, Bonsoir stares us in the face as almost a relic from the past – an anomaly which seems out of place and out of date in this era of mindless social media sharing and AI. At its peak it held out the promise of a truly successful cultural initiative, and for a good many decades, through Sri Lanka’s most turbulent, violent periods, it brought an entire culture and a society on to Sri Lankan television screens – all the way, to quote Kumar, from Colombo to Girandurukotte.

It goes without saying that no other European country based here came up with as successful a programme as Bonsoir. The result is that, today, on the cultural diplomacy front, the French have surpassed many of their European partners in Sri Lanka. This aspect of Bonsoir often gets missed out, but it is the one aspect which made the programme, and its many faces – Kumar, Yasmin, and others – stand out.

Life was simple those days, and I am happy lived through them. Bonsoir was a part of my growing up, but we were the last generation which could appreciate such programmes. Today life is fixated on the moment, the here and now, the five minutes of fame that eclipses everything else before dying and withering away. One wishes for a time where cultural shows truly delivered. Bonsoir was such a programme. The greatest tribute one can pay to it, in that sense, it that it will never be replicated: not now, not ever.